Section 4.5 Slope-Intercept Form

In this section, we will explore one of the “standard” ways to write the equation of a line. It's known as slope-intercept form.

Subsection 4.5.1 Slope-Intercept Definition

Recall Example 4.4.4, where Yara had \(\$50\) in her savings account when the year began, and decided to deposit \(\$20\) each week without withdrawing any money. In that example, we model using \(x\) to represent how many weeks have passed. After \(x\) weeks, Yara has added \(20x\) dollars. And since she started with \(\$50\text{,}\) she has

in her account after \(x\) weeks. In this example, there is a constant rate of change of \(20\) dollars per week, so we call that the slope as discussed in Section 4.4. We also saw in Figure 4.4.6 that plotting Yara's balance over time gives us a straight-line graph.

The graph of Yara's savings has some things in common with almost every straight-line graph. There is a slope and there is a place where the line crosses the \(y\)-axis. Figure 4.5.1 illustrates this in the abstract.

We already have an accepted symbol, \(m\text{,}\) for the slope of a line. The \(y\)-intercept is a point on the \(y\)-axis where the line crosses. Since it's on the \(y\)-axis, the \(x\)-coordinate of this point is \(0\text{.}\) It is standard to call the \(y\)-intercept \((0,b)\) where \(b\) represents the position of the \(y\)-intercept on the \(y\)-axis.

Checkpoint 4.5.2.

Use Figure 4.4.6 to answer this question.

One way to write the equation for Yara's savings was

where both \(m=20\) and \(b=50\) are immediately visible in the equation. Now we are ready to generalize this.

Definition 4.5.3. Slope-Intercept Form.

When \(x\) and \(y\) have a linear relationship where \(m\) is the slope and \((0,b)\) is the \(y\)-intercept, one equation for this relationship is

and this equation is called the slope-intercept form of the line. It is called this because the slope and \(y\)-intercept are immediately discernible from the numbers in the equation.

Checkpoint 4.5.4.

Remark 4.5.5.

The number \(b\) is the \(y\)-value when \(x=0\text{.}\) Therefore, it is common to refer to \(b\) as the initial value or starting value of a linear relationship.

Example 4.5.6.

With a simple equation like \(y=2x+3\text{,}\) we can see that this is a line whose slope is \(2\) and which has initial value \(3\text{.}\) So starting at \(y=3\) when \(x=0\) (that is, on the \(y\)-axis), each time we increase the \(x\)-value by \(1\text{,}\) the \(y\)-value increases by \(2\text{.}\) With these basic observations, we can quickly produce a table and/or a graph.

| \(x\) | \(y\) | ||

| start on \(y\)-axis \(\longrightarrow\) |

\(0\) | \(3\) | initial \(\longleftarrow\) value |

| increase by \(1\longrightarrow\) |

\(1\) | \(5\) | increase \(\longleftarrow\) by \(2\) |

| increase by \(1\longrightarrow\) |

\(2\) | \(7\) | increase \(\longleftarrow\) by \(2\) |

| increase by \(1\longrightarrow\) |

\(3\) | \(9\) | increase \(\longleftarrow\) by \(2\) |

| increase by \(1\longrightarrow\) |

\(4\) | \(11\) | increase \(\longleftarrow\) by \(2\) |

Example 4.5.7.

Decide whether data in the table has a linear relationship. If so, write the linear equation in slope-intercept form.

| \(x\)-values | \(y\)-values |

| \(0\) | \(-4\) |

| \(2\) | \(2\) |

| \(5\) | \(11\) |

| \(9\) | \(23\) |

To assess whether the relationship is linear, we have to recall from Section 4.3 that we should examine rates of change between data points. Note that the changes in \(y\)-values are not consistent. However, the rates of change are calculated as follows:

When \(x\) increases by \(2\text{,}\) \(y\) increases by \(6\text{.}\) The first rate of change is \(\frac{6}{2}=3\text{.}\)

When \(x\) increases by \(3\text{,}\) \(y\) increases by \(9\text{.}\) The second rate of change is \(\frac{9}{3}=3\text{.}\)

When \(x\) increases by \(4\text{,}\) \(y\) increases by \(12\text{.}\) The third rate of change is \(\frac{12}{4}=3\text{.}\)

Since the rates of change are all the same, \(3\text{,}\) the relationship is linear and the slope \(m\) is \(3\text{.}\)

According to the table, when \(x=0\text{,}\) \(y=-4\text{.}\) So the starting value, \(b\text{,}\) is \(-4\text{.}\)

So in slope-intercept form, the line's equation is \(y=3x-4\text{.}\)

Checkpoint 4.5.8.

Subsection 4.5.2 Graphing Slope-Intercept Equations

Example 4.5.9.

The conversion formula for a Celsius temperature into Fahrenheit is \(F=\frac{9}{5}C+32\text{.}\) This appears to be in slope-intercept form, except that \(x\) and \(y\) are replaced with \(C\) and \(F\text{.}\) Suppose you are asked to graph this equation. How will you proceed? You could make a table of values as we do in Section 4.2, but that takes time and effort. Since the equation here is in slope-intercept form, there is a nicer way.

Since this equation is for starting with a Celsius temperature and obtaining a Fahrenheit temperature, it makes sense to let \(C\) be the horizontal axis variable and \(F\) be the vertical axis variable. Note the slope is \(\frac{9}{5}\) and the vertical intercept (here, the \(F\)-intercept) is \((0,32)\text{.}\)

Set up the axes using an appropriate window and labels. Considering the freezing and boiling temperatures of water, it's reasonable to let \(C\) run through at least \(0\) to \(100\text{.}\) Similarly it's reasonable to let \(F\) run through at least \(32\) to \(212\text{.}\)

Plot the \(F\)-intercept, which is at \((0,32)\text{.}\)

Starting at the \(F\)-intercept, use slope triangles to reach the next point. Since our slope is \(\frac{9}{5}\text{,}\) that suggests a “run” of \(5\) and a “rise” of \(9\) might work. But as Figure 4.5.10 indicates, such slope triangles are too tiny. Since \(\frac{9}{5}=\frac{90}{50}\text{,}\) we can try a “run” of \(50\) and a rise of \(90\text{.}\)

Connect your points with a straight line, use arrowheads, and label the equation.

Example 4.5.11.

Graph \(y=-\frac{2}{3}x+10\text{.}\)

Example 4.5.13.

Graph \(y=3x+5\text{.}\)

Subsection 4.5.3 Writing a Slope-Intercept Equation Given a Graph

We can write a linear equation in slope-intercept form based on its graph. We need to be able to calculate the line's slope and see its \(y\)-intercept.

Checkpoint 4.5.15.

Checkpoint 4.5.16.

Subsection 4.5.4 Writing a Slope-Intercept Equation Given Two Points

The idea that any two points uniquely determine a line has been understood for thousands of years in many cultures around the world. Once you have two specific points, there is a straightforward process to find the slope-intercept form of the equation of the line that connects them.

Example 4.5.17.

Find the slope-intercept form of the equation of the line that passes through the points \((0,5)\) and \((8,-5)\text{.}\)

We are trying to write down \(y=mx+b\text{,}\) but with specific numbers for \(m\) and \(b\text{.}\) So the first step is to find the slope, \(m\text{.}\) To do this, recall the slope formula from Section 4.4. It says that if a line passes through the points \((x_1,y_1)\) and \((x_2,y_2)\text{,}\) then the slope is found by the formula \(m=\frac{y_2-y_1}{x_2-x_1}\text{.}\)

Applying this to our two points \((\overset{x_1}{0},\overset{y_1}{5})\) and \((\overset{x_2}{8},\overset{y_2}{-5})\text{,}\) we see that the slope is:

We are trying to write \(y=mx+b\text{.}\) Since we already found the slope, we know that we want to write \(y=-\frac{5}{4}x+b\text{,}\) but we need a specific number for \(b\text{.}\) We happen to know that one point on this line is \((0,5)\text{,}\) which is on the \(y\)-axis because its \(x\)-value is \(0\text{.}\) So \((0,5)\) is this line's \(y\)-intercept, and therefore \(b=5\text{.}\) (We're only able to make this conclusion because this point has \(0\) for its \(x\)-coordinate.) So, our equation is

Example 4.5.18.

Find the slope-intercept form of the equation of the line that passes through the points \((3,-8)\) and \((-6,1)\text{.}\)

The first step is always to find the slope between our two points: \((\overset{x_1}{3},\overset{y_1}{-8})\) and \((\overset{x_2}{-6},\overset{y_2}{1})\text{.}\) Using the slope formula again, we have:

Now that we have the slope, we can write \(y=-1x+b\text{,}\) which simplifies to \(y=-x+b\text{.}\) Unlike in Example 4.5.17, we are not given the value of \(b\) because neither of our two given points have an \(x\)-value of \(0\text{.}\) The trick to finding \(b\) is to remember that we have two points that we know make the equation true! This means all we have to do is substitute either point into the equation for \(x\) and \(y\) and solve for \(b\text{.}\) Let's arbitrarily choose \((3,-8)\) to plug in.

In conclusion, the equation for which we were searching is \(y=-x-5\text{.}\)

Don't be tempted to plug in values for \(x\) and \(y\) at this point. The general equation of a line in any form should have (at least one, and in this case two) variables in the final answer.

Checkpoint 4.5.19.

Checkpoint 4.5.20.

Subsection 4.5.5 Modeling with Slope-Intercept Form

We can model many relatively simple relationships using slope-intercept form and then solve related questions using algebra. Here are a few examples.

Example 4.5.21.

Uber is a ride-sharing company. Its pricing in Portland factors in how much time and how many miles a trip takes. But if you assume that rides average out at a speed of 30 mph, then their pricing scheme boils down to a base of \(\$7.35\) for the trip, plus \(\$3.85\) per mile. Use a slope-intercept equation and algebra to answer these questions.

How much is the fare if a trip is \(5.3\) miles long?

With \(\$100\) available to you, how long of a trip can you afford?

The rate of change (slope) is \(\$3.85\) per mile and the starting value is \(\$7.35\text{.}\) So the slope-intercept equation is

In this equation, \(x\) stands for the number of miles in a trip and \(y\) stands for the amount of money to be charged.

If a trip is \(5\) miles long, we substitute \(x=5\) into the equation and we have:

And the \(5\)-mile ride will cost you about \(\$26.60\text{.}\) (We say “about,” because this was all assuming you average 30 mph.)

Next, to find how long of a trip would cost \(\$100\text{,}\) we substitute \(y=100\) into the equation and solve for \(x\text{:}\)

So with \(\$100\) you could afford a little more than a \(24\)-mile trip.

Checkpoint 4.5.22.

Exercises 4.5.6 Exercises

Review and Warmup

1.

Evaluate \({5a-6A}\) for \(a = 1\) and \(A = -6\text{.}\)

2.

Evaluate \({-4b+8a}\) for \(b = 9\) and \(a = 10\text{.}\)

3.

Evaluate

for \(x_1 = -5\text{,}\) \(x_2 = 13\text{,}\) \(y_1 = -6\text{,}\) and \(y_2 = 7\text{:}\)

4.

Evaluate

for \(x_1 = -1\text{,}\) \(x_2 = 12\text{,}\) \(y_1 = -4\text{,}\) and \(y_2 = -6\text{:}\)

Identifying Slope and \(y\)-Intercept

5.

Find the line’s slope and \(y\)-intercept.

A line has equation \(y={7}x+2\text{.}\)

This line’s slope is .

This line’s \(y\)-intercept is .

6.

Find the line’s slope and \(y\)-intercept.

A line has equation \(y={8}x+8\text{.}\)

This line’s slope is .

This line’s \(y\)-intercept is .

7.

Find the line’s slope and \(y\)-intercept.

A line has equation \(y={-3}x - 6\text{.}\)

This line’s slope is .

This line’s \(y\)-intercept is .

8.

Find the line’s slope and \(y\)-intercept.

A line has equation \(y={-2}x - 10\text{.}\)

This line’s slope is .

This line’s \(y\)-intercept is .

9.

Find the line’s slope and \(y\)-intercept.

A line has equation \(y=x - 9\text{.}\)

This line’s slope is .

This line’s \(y\)-intercept is .

10.

Find the line’s slope and \(y\)-intercept.

A line has equation \(y=x - 7\text{.}\)

This line’s slope is .

This line’s \(y\)-intercept is .

11.

Find the line’s slope and \(y\)-intercept.

A line has equation \(y=-x - 5\text{.}\)

This line’s slope is .

This line’s \(y\)-intercept is .

12.

Find the line’s slope and \(y\)-intercept.

A line has equation \(y=-x - 3\text{.}\)

This line’s slope is .

This line’s \(y\)-intercept is .

13.

Find the line’s slope and \(y\)-intercept.

A line has equation \(\displaystyle{ y= -\frac{4}{5}x +1 }\text{.}\)

This line’s slope is .

This line’s \(y\)-intercept is .

14.

Find the line’s slope and \(y\)-intercept.

A line has equation \(\displaystyle{ y= -\frac{6}{7}x - 6 }\text{.}\)

This line’s slope is .

This line’s \(y\)-intercept is .

15.

Find the line’s slope and \(y\)-intercept.

A line has equation \(\displaystyle{ y= \frac{1}{2}x +8 }\text{.}\)

This line’s slope is .

This line’s \(y\)-intercept is .

16.

Find the line’s slope and \(y\)-intercept.

A line has equation \(\displaystyle{ y= \frac{1}{4}x - 7 }\text{.}\)

This line’s slope is .

This line’s \(y\)-intercept is .

17.

Find the line’s slope and \(y\)-intercept.

A line has equation \(\displaystyle{ y= 9 +{10}x }\text{.}\)

This line’s slope is .

This line’s \(y\)-intercept is .

18.

Find the line’s slope and \(y\)-intercept.

A line has equation \(\displaystyle{ y= 2 +{2}x }\text{.}\)

This line’s slope is .

This line’s \(y\)-intercept is .

19.

Find the line’s slope and \(y\)-intercept.

A line has equation \(\displaystyle{ y= 2 -x }\text{.}\)

This line’s slope is .

This line’s \(y\)-intercept is .

20.

Find the line’s slope and \(y\)-intercept.

A line has equation \(\displaystyle{ y= 3 -x }\text{.}\)

This line’s slope is .

This line’s \(y\)-intercept is .

Graphs and Slope-Intercept Form

21.

Graph the equation \(y=4x\text{.}\)

22.

Graph the equation \(y=5x\text{.}\)

23.

Graph the equation \(y=-3x\text{.}\)

24.

Graph the equation \(y=-2x\text{.}\)

25.

Graph the equation \(y=\frac{5}{2}x\text{.}\)

26.

Graph the equation \(y=\frac{1}{4}x\text{.}\)

27.

Graph the equation \(y=-\frac{1}{3}x\text{.}\)

28.

Graph the equation \(y=-\frac{5}{4}x\text{.}\)

29.

Graph the equation \(y=5x+2\text{.}\)

30.

Graph the equation \(y=3x+6\text{.}\)

31.

Graph the equation \(y=-4x+3\text{.}\)

32.

Graph the equation \(y=-2x+5\text{.}\)

33.

Graph the equation \(y=x-4\text{.}\)

34.

Graph the equation \(y=x+2\text{.}\)

35.

Graph the equation \(y=-x+3\text{.}\)

36.

Graph the equation \(y=-x-5\text{.}\)

37.

Graph the equation \(y=\frac{2}{3}x+4\text{.}\)

38.

Graph the equation \(y=\frac{3}{2}x-5\text{.}\)

39.

Graph the equation \(y=-\frac{3}{5}x-1\text{.}\)

40.

Graph the equation \(y=-\frac{1}{5}x+1\text{.}\)

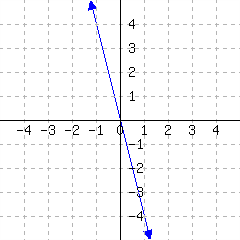

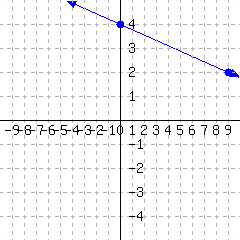

41.

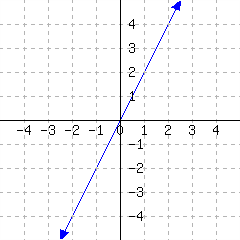

A line’s graph is given. What is this line’s slope-intercept equation?

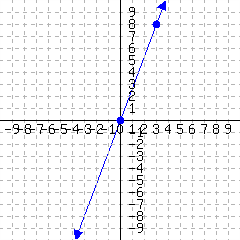

42.

A line’s graph is given. What is this line’s slope-intercept equation?

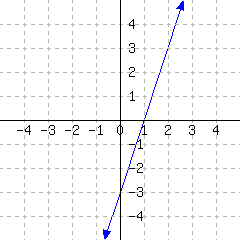

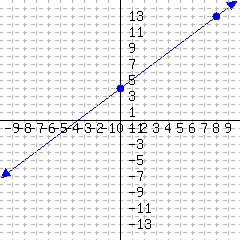

43.

A line’s graph is given. What is this line’s slope-intercept equation?

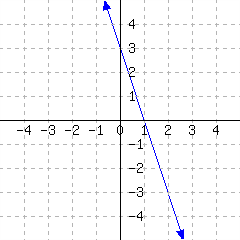

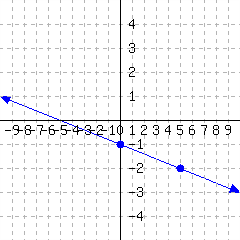

44.

A line’s graph is given. What is this line’s slope-intercept equation?

45.

A line’s graph is given. What is this line’s slope-intercept equation?

46.

A line’s graph is given. What is this line’s slope-intercept equation?

47.

A line’s graph is given. What is this line’s slope-intercept equation?

48.

A line’s graph is given. What is this line’s slope-intercept equation?

Writing a Slope-Intercept Equation Given Two Points

49.

Find the following line’s equation in slope-intercept form.

The line passes through the points \((2,14)\) and \((3,17)\text{.}\)

50.

Find the following line’s equation in slope-intercept form.

The line passes through the points \((4,17)\) and \((1,8)\text{.}\)

51.

Find the following line’s equation in slope-intercept form.

The line passes through the points \((-5,11)\) and \((5,-29)\text{.}\)

52.

Find the following line’s equation in slope-intercept form.

The line passes through the points \((2,-1)\) and \((5,-10)\text{.}\)

53.

Find the following line’s equation in slope-intercept form.

The line passes through the points \((-1,5)\) and \((4,0)\text{.}\)

54.

Find the following line’s equation in slope-intercept form.

The line passes through the points \((-5,12)\) and \((-2,9)\text{.}\)

55.

A line passes through the points \((2,10)\) and \((3,15)\text{.}\) Find this line’s equation in slope-intercept form.

This line’s slope-intercept equation is .

56.

A line passes through the points \((-4,8)\) and \((5,-10)\text{.}\) Find this line’s equation in slope-intercept form.

This line’s slope-intercept equation is .

57.

Find the following line’s equation in slope-intercept form.

The line passes through the points \((-18,{2})\) and \((27,{12})\text{.}\)

58.

Find the following line’s equation in slope-intercept form.

The line passes through the points \((21,{19})\) and \((-14,{4})\text{.}\)

59.

Find the following line’s equation in slope-intercept form.

The line passes through the points \((21,{-3})\) and \((7,{5})\text{.}\)

60.

Find the following line’s equation in slope-intercept form.

The line passes through the points \((-9,{13})\) and \((27,{-7})\text{.}\)

Applications

61.

A gym charges members \({\$30}\) for a registration fee, and then \({\$32}\) per month. You became a member some time ago, and now you have paid a total of \({\$350}\) to the gym. How many months have passed since you joined the gym?

months have passed since you joined the gym.

62.

Your cell phone company charges a \({\$24}\) monthly fee, plus \({\$0.13}\) per minute of talk time. One month your cell phone bill was \({\$79.90}\text{.}\) How many minutes did you spend talking on the phone that month?

You spent talking on the phone that month.

63.

A school purchased a batch of T-shirts from a company. The company charged \({\$9}\) per T-shirt, and gave the school a \({\$95}\) rebate. If the school had a net expense of \({\$2{,}605}\) from the purchase, how many T-shirts did the school buy?

The school purchased T-shirts.

64.

Ross hired a face-painter for a birthday party. The painter charged a flat fee of \({\$100}\text{,}\) and then charged \({\$4.50}\) per person. In the end, Ross paid a total of \({\$185.50}\text{.}\) How many people used the face-painter’s service?

people used the face-painter’s service.

65.

A certain country has \(89.6\) million acres of forest. Every year, the country loses \(1.28\) million acres of forest mainly due to deforestation for farming purposes. If this situation continues at this pace, how many years later will the country have only \(29.44\) million acres of forest left? (Use an equation to solve this problem.)

After years, this country would have \(29.44\) million acres of forest left.

66.

Teresa has \({\$73}\) in her piggy bank. She plans to purchase some Pokemon cards, which costs \({\$2.25}\) each. She plans to save \({\$34.75}\) to purchase another toy. At most how many Pokemon cards can he purchase?

Write an equation to solve this problem.

Teresa can purchase at most Pokemon cards.

67.

By your cell phone contract, you pay a monthly fee plus \({\$0.04}\) for each minute you spend on the phone. In one month, you spent \(280\) minutes over the phone, and had a bill totaling \({\$26.20}\text{.}\)

Let \(x\) be the number of minutes you spend on the phone in a month, and let \(y\) be your total cell phone bill for that month, in dollars. Use a linear equation to model your monthly bill based on the number of minutes you spend on the phone.

This line’s slope-intercept equation is .

If you spend \(180\) minutes on the phone in a month, you would be billed .

If your bill was \({\$33.00}\) one month, you must have spent minutes on the phone in that month.

68.

A company set aside a certain amount of money in the year 2000. The company spent exactly \({\$31{,}000}\) from that fund each year on perks for its employees. In \(2002\text{,}\) there was still \({\$605{,}000}\) left in the fund.

Let \(x\) be the number of years since 2000, and let \(y\) be the amount of money, in dollars, left in the fund that year. Use a linear equation to model the amount of money left in the fund after so many years.

The linear model’s slope-intercept equation is .

In the year \(2011\text{,}\) there was left in the fund.

In the year , the fund will be empty.

69.

A biologist has been observing a tree’s height. This type of tree typically grows by \(0.2\) feet each month. Thirteen months into the observation, the tree was \(20.2\) feet tall.

Let \(x\) be the number of months passed since the observations started, and let \(y\) be the tree’s height at that time, in feet. Use a linear equation to model the tree’s height as the number of months pass.

This line’s slope-intercept equation is .

\(29\) months after the observations started, the tree would be feet in height.

months after the observation started, the tree would be \(28.4\) feet tall.

70.

Scientists are conducting an experiment with a gas in a sealed container. The mass of the gas is measured, and the scientists realize that the gas is leaking over time in a linear way. Each minute, they lose \(5.3\) grams. Ten minutes since the experiment started, the remaining gas had a mass of \(190.8\) grams.

Let \(x\) be the number of minutes that have passed since the experiment started, and let \(y\) be the mass of the gas in grams at that moment. Use a linear equation to model the weight of the gas over time.

This line’s slope-intercept equation is .

\(38\) minutes after the experiment started, there would be grams of gas left.

If a linear model continues to be accurate, minutes since the experiment started, all gas in the container will be gone.

71.

A company set aside a certain amount of money in the year 2000. The company spent exactly the same amount from that fund each year on perks for its employees. In 2003, there was still \({\$527{,}000}\) left in the fund. In 2006, there was \({\$404{,}000}\) left.

Let \(x\) be the number of years since 2000, and let \(y\) be the amount of money, in dollars, left in the fund that year. Use a linear equation to model the amount of money left in the fund after so many years.

Find the linear model’s slope-intercept equation.

In the year 2011, how much money was left in the fund?

Determine in what year, the fund will be empty.

72.

By your cell phone contract, you pay a monthly fee plus some money for each minute you use the phone during the month. In one month, you spent 280 minutes on the phone, and paid \({\$32.40}\). In another month, you spent 320 minutes on the phone, and paid \({\$34.60}\).

Let \(x\) be the number of minutes you talk over the phone in a month, and let \(y\) be your cell phone bill, in dollars, for that month. Use a linear equation to model your monthly bill based on the number of minutes you talk over the phone.

Find this linear model’s slope-intercept equation.

If you spent 180 minutes over the phone in a month, how much you would pay?

If in a month, you paid \({\$44.50}\) for your cell phone bill, how many minutes must you have spent on the phone in that month?

73.

Scientists are conducting an experiment with a gas in a sealed container. The mass of the gas is measured, and the scientists realize that the gas is leaking over time in a linear way.

Six minutes since the experiment started, the gas had a mass of 215.6 grams.

Eighteen minutes since the experiment started, the gas had a mass of 156.8 grams.

Let \(x\) be the number of minutes that have passed since the experiment started, and let \(y\) be the mass of the gas in grams at that moment. Use a linear equation to model the weight of the gas over time.

Find this line’s slope-intercept equation.

37 minutes after the experiment started, how many grams of gas will be left?

If a linear model continues to be accurate, after how many minutes since the experiment started, will all gas in the container be gone?

74.

A biologist has been observing a tree’s height. 13 months into the observation, the tree was 12.9 feet tall. 18 months into the observation, the tree was 13.4 feet tall.

Let \(x\) be the number of months passed since the observations started, and let \(y\) be the tree’s height at that time, in feet. Use a linear equation to model the tree’s height as the number of months pass.

Find this line’s slope-intercept equation.

29 months after the observations started, how tall would the tree be?

How many months after the observation started, will the tree reach 17.6 feet tall?

Challenge

75.

Line \(S\) has the equation \(y = ax + b\) and Line \(T\) has the equation \(y =cx + d\text{.}\) Suppose \(a \gt b \gt c \gt d \gt 0 \text{.}\)

What can you say about Line \(S\) and Line \(T\text{,}\) given that \(a \gt c\text{?}\) Give as much information about Line \(S\) and Line \(T\) as possible.

What can you say about Line \(S\) and Line \(T\text{,}\) given that \(b \gt d\text{?}\) Give as much information about Line \(S\) and Line \(T\) as possible.